Low Earth Orbit

Roughly three months ago, I got together with my friends Scott and Steve, and we started a podcast: Low Earth Orbit.

I thought it would be interesting to look behind the scenes of Low Earth Orbit. Inspired by This American Life and their excellent comic about their production process, Radio: An Illustrated Guide, I’ll outline the life of a typical episode from concept to completion.

Choosing

Every episode starts out as a humble topic suggestion.

We use a private wiki to collaborate on various parts of the show, and we have several pages in the wiki dedicated to topic brainstorming. We segregate the topics into broad categories: movies, games, book, and everything else.

Whenever possible, we try to review things soon after they’re released. Movies are the easiest: they have a release date that we know about well in advance (usually on a Friday), it only takes a few hours to watch the film, we can record on Saturday or Sunday and then post the episode on Tuesday. By the time the MP3 lands on a listener’s device, the movie is still a very fresh topic.

Such promptness is harder with games, but not impossible. We reviewed the latest SimCity back in September: it was released on a Thursday and we had our review published on Tuesday.

The real difference between games and movies is the time commitment. The Last of Us, a recent PlayStation 3 game, takes roughly 15 hours to complete. Compare that to the not-quite-2-hours of the Ender’s Game movie. It’s logistically and physically impossible for me to do anything for 15 hours straight, so it takes multiple days to play a game to completion. For most of our game reviews, we’ve had to pass judgement without having seen the end, simply because we don’t have time to get there.

So far we’ve only done one book episode (and it was really a comic series, not a novel), but I imagine that they would have an even larger time cost than video games.

Ultimately, we choose topics based on what all three of us are interested in and can commit time to reviewing. Scheduling is a lot more important here than you might guess: being able to predict far in advance what topics we’ll be covering helps make the whole production feel less rushed.

Recording

Barring any scheduling conflicts, we usually record on Sundays.

There’s no secret formula here, it just works out well for everyone: all three of us are usually free on Sunday evening.

We’ve recorded at all three of our apartments. So far, the Voss place has hosted the most, because our spare bedroom converts into a recording studio much better than anyone expected.

Our setup is pretty simple: a laptop, a Yeti microphone, and the three of us huddled around it. I have some wild idea that someday we’ll each have our own mic and be sitting in real sound booths, like an honest-to-god radio show, but we haven’t reached that level of crazy yet. The multiple-mic setup would be handy, though, because I think it would give us more options during editing: for example, the volume of each host’s voice could be adjusted independently.

The “one weird trick” to getting good audio outside of a professional studio is to get rid of echoes. You can shell out big money for fancy audio foam panels, but blankets and clothes work fine, too: even Randall Beach, “The Voice of NPR,” did all his recordings in a coat closet.

We do three things to our room to get it into studio-mode:

-

We take the fuzziest blanket we have and drape it over the desk, then set the microphone on top. This helps eliminate echo from the desk surface.

-

A very generous coworker donated two fancy-pants audio foam panels to us, and we place these right behind the microphone. This prevents echoes from the computer monitor and wall behind the desk.

-

We drape blankets over some custom PVC frames that I built, and position those stands behind and around our chairs, as closely as we comfortably can.

Those PVC frames have been amazing. They were cheap and easy to build, and they deliver great results. The construction is simple enough: they’re basically just big rectangles with feet.

The blankets are held in place with a few clamps at the top.

It’s hard to see from these photos, but this room is especially nice because it has a carpeted floor, a daybed in the corner with a fluffy comforter, and no noisy appliances like a refrigerator or air conditioner.

Editing

Scott does all the editing in Logic Pro X.

I can’t claim to know much about this area, but I do know that one of the things we do to our audio is apply compression. Unfortunately, the word “compression” means a lot of different things in different contexts. In this case I’m talking about dynamic range compression, which basically means “the softest sound and the loudest sound shouldn’t be that different.”

For example, in our first few episodes, it was a bit hard to hear us when we were speaking normally, but then it was ear-splittingly loud when we would laugh. That’s because the dynamic range was large: the soft speaking sounds were much quieter than the loud laughing sounds. Using compression makes the dynamic range smaller: the speaking becomes louder and the laughing quieter, so our listeners don’t have to constantly adjust the volume.

It’s possible to use software filters to remove background noise and echo, but it’s much easier to just record better audio in the first place by moving to a different room or setting up blankets.

Publishing

The technical details of publishing a podcast, from hosting MP3 files to writing the RSS feed, are easy to find so I won’t reiterate them here.

Our website is created with Jekyll, a tool for building websites entirely from static files. Jekyll is a very nerdy way to publish a website, but I like it because it’s so easy to manage. There’s no server process to monitor, no database to back up, no fear that a link from Daring Fireball will bring down the server, just a directory of static HTML files.

To streamline the process, I wrote some shell scripts for creating episode files

in Jekyll and publishing the site to the server. These scripts are basically

just wrappers around curl and rsync but sometimes that’s all you need to be useful.

The MP3 files themselves are hosted on Amazon S3 because, well, everything is on Amazon Web Services these days. And because it’s reliable: we don’t have to worry about it going down, or exceeding our bandwidth quota. And it’s cheap. Hypothetically we could use a CDN like CloudFront for even faster downloads, but I don’t think anyone is complaining about our download speed.

We embed an inline audio player using audio.js. This makes it easier for website visitors who aren’t subscribers to listen to individual episodes.

Measuring

I have a charts-and-graphs problem. Like a “the first step is admitting you have a problem” problem.

Naturally, I want to be able to track as many stats as possible about the show. How many listeners do we have? Which episodes are the most popular? How are people finding out about us?

Unfortunately, it’s pretty hard to measure that for podcasts.

The website is easy to track: throw Google Analytics in there and you can find out 99% of what you want to know. Tracking the audio is harder: you’re basically reduced to parsing through Apache logs, looking at user-agents and IP addresses to guess how many unique listeners there are.

That’s not to say there are no useful insights to be had from server logs. Using those logs, we’re able to estimate both the number of subscribers (aka, people who have added Low Earth Orbit to iTunes or Instacast or what have you) and to estimate how many listens each episode is getting. Those two numbers aren’t the same because a non-subscriber can listen to individual episodes on our website, which increases the number of listens but not the number of subscribers.

I wrote a set of Python scripts to gather up all this data and format it nicely. Every night, these scripts publish a web page with pretty charts and graphs of listens, and send me an email with subscriber numbers.

Tracking subscribers is easy enough with 2000s-era techniques: look at the

Apache request logs for /podcast.xml and count up the requests, using the IP

address and user-agent to prevent duplicates. I also do some filtering based on

user-agent to exclude things that may request our RSS feed but aren’t really

people: for example, I exclude the Googlebot and the iTunes Store servers.

Tracking downloads is just as simple: for each MP3, take the total number of outgoing bytes and divide it by the number of bytes in the file. It’s possible to parse the S3 logs yourself, but we use Qloudstat to do that for us and access their JSON API instead.

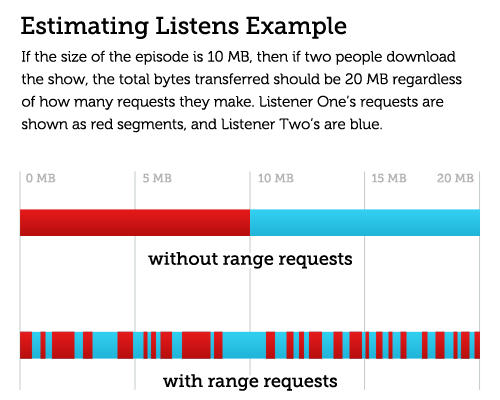

You may be wondering “why don’t you just count the number of requests for each MP3?” We can’t do that because some podcast apps use range requests to download the episodes, which means they download the file in many small chunks instead of one big request. A single user listening to a single episode may make hundreds of requests. But, they probably won’t download the same data twice (or at least, they won’t do that very often), so the “total bytes divided by filesize” trick gets us in the ballpark.

There are about a million other things I would love to be able to measure but they either aren’t technically possible or would require us to stop using Jekyll, so I’ll settle for these two stats for now.

Marketing

Almost all of our website traffic comes from Twitter.

We have an official show Twitter account, @lowearthshow. Every episode gets tweeted at least once, and we’ve even had some high-profile retweets: when we posted our first SimCity episode, the general manager of Maxis Emeryville retweeted us.

Other than announcing episodes on social media, I’ll admit that I have no idea how to promote a podcast. I don’t think we have any world-domination plans: I certainly don’t think we’ll get as big as juggernauts like Radiolab or This American Life, but it’s fun to see our audience slowly grow.

Future-ing

So, what’s next for Low Earth Orbit? I don’t know.

Podcasting as a whole seems like it’s heating up again. People are talking about podcasts more, several well-known developers are working on podcast apps, and the tools for creating audio have never been better. It’s a new golden age.

All I know for sure is that now is a very exciting time to be a podcast listener and a podcast creator.